Disclaimer: This post is sponsored by GroundFloor.com.

Opinions expressed herein are my own.

I am not an investor in GroundFloor.

Getting in on the Ground Floor: investing directly in the platform.

There’s a certain honor in business to “eating your own dogfood”; actually using the product or service that your company sells.

So, if you’re running an investment crowdfunding platform, and you want to raise a round of investor money to expand your business, it makes sense to crowdfund it.

In this spirit, Groundfloor has become the latest investment crowdfunding platform to launch a self-funding campaign to raise equity investment directly from its user base instead of from outside institutional investors.

As an investor, it’s an interesting proposition. Here’s why:

Fertile Ground

Excluding P2P lending or ICOs, which it would be a stretch to call crowdfunding, there has so far been only one part of the nascent investment crowdfunding market reliably producing solid returns for investors. That’s real estate crowdfunding. Real estate crowdfunding sites give investors the opportunity to buy into a development project, either in the form of ownership equity or as secured debt, without the hassle of being a real estate developer themselves.

Groundfloor.com provides an online investment platform which enables non-accredited investors to buy into individual secured real estate loans that pay returns averaging 10-14%, which is consistent with the rest of the real estate crowdfunding industry.

For example:

- Fundrise tracks an 8.76%-12.42% average annual return for their investors since 2014.

- PatchOfLand’s website invites investors to “earn up to 12%” on their real estate investment platform.

- EarlyShares projects an 18% IRR.

- Realty Mogul shows IRR of 12-36% on its past investments.

- RealCrowd targets an IRR of 8-30% on its offerings.

(though each of these platforms has somewhat different fee and asset structures)

The appeal as an investor is clear. It’s nice to invest in real estate in small amounts, without realtors, zoning, tenants, and late night calls to fix a clogged sink.

In this way, real estate crowdfunding is similar to investing in an REIT. The primary differences are that with crowdfunding, rather than buying into a huge portfolio, you choose the particular properties or loans to invest in and can handpick the opportunities that look best to you and best fit your risk/return appetite. Also, crowdfunded real estate is not a security traded on a liquid market, so you don’t risk losing your principal when the stock market crashes — a good diversification from the stress of watching the Dow.

A 2016 industry report estimated that year’s overall total US real estate crowdfunding activity at $3.5 billion. The platform RealtyShares alone reports having driven $700 million in real estate crowdfunding activity to date, Patch of Land tallies $489 million in real estate loans originated, RealtyMogul reports over $300 million invested via their platform, and FundRise claims $210 million, while GroundFloor itself originated $54 million in loans. Given the other dozen or so active real estate investment crowdfunding platforms out there, the $3.5 billion estimate feels like a reasonable number.

Startup Crowdfunding is Off to a Slow Start:

On the other hand, equity crowdfunding, or buying equity shares of startup companies through platforms such as MicroVentures, StartEngine, and SeedInvest, has so far not produced much in the way of returns for their early adopters.

While a few big platforms, like AngelList and CircleUp, provide a rich ecosystem of startup dealflow for accredited “angel” investors, the online platforms enabled by the JOBS Act to make investing in small startups possible for everyone have had anemic activity.

The one high profile all-investor equity crowdfunding raise that has actually had a liquidity for investors was Elio Motors, an aspiring manufacturer of three-wheeled electric vehicles, which initially raised $16 million dollars on StartEngine, and then listed their shares on OTC markets, where they promptly dropped from $40 to under $3. Elio Motors was recently reported by Crowdfund Insider to be out of money.

Crowdfund Capital Advisors, a legal and advisory group instrumental in getting the JOBS Act passed, estimates that total equity crowdfunding investment raised has been about $100 million so far via “Regulation CF,” while Stradling’s crowdfunding report counts another $236.5 million in “Regulation A” crowdfunding activity during 2017.

Combined, we see about a $350 million market in equity startup crowdfunding activity, or 10% of the $3.5 billion annual rate for real estate crowdfunding.

(Note: for comparison, cryptocurrency/token ICOs raised about $6 billion in 2017.)

This is why Groundfloor’s raise is so interesting. It’s the intersection of these two parts of the market, an equity crowdfunding raise for buying shares in a real estate debt crowdfunding platform. It’s like going to the grocery store to buy milk and coming home with a baby cow instead.

The Basics:

Groundfloor invites its users to contribute to real estate loans that range in size from $75,000 to $2,000,000 through Groundfloor’s online platform at rates of 5-25%, with rate of return varying based on length of loan. Groundfloor offers 3, 6, 9, and 12 month loans, with the highest returns on the 12 month loans.

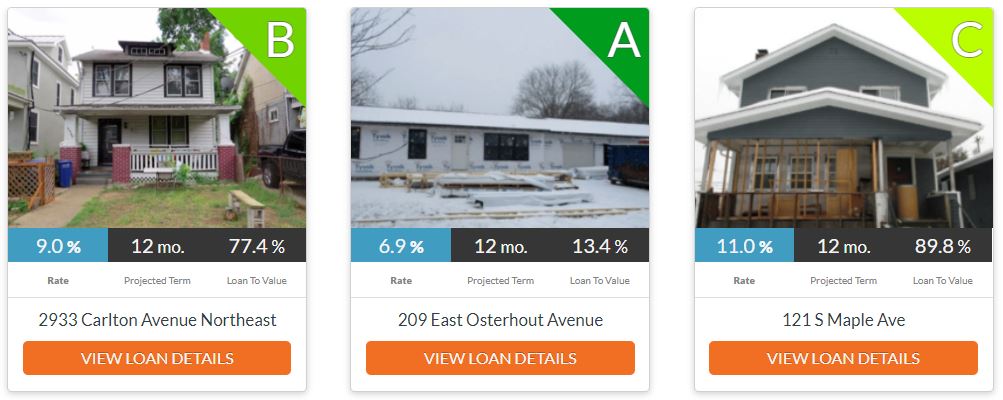

Examples:

These loans go to experienced real estate developers that are buying single family and multi-family homes and fixing them up. As an investor on the platform, you see the property, the interest rate offered, and other specifics of the loan. The standard approach is to diversify your investment out over several projects.

Groundfloor is based in Atlanta, Georgia, was founded in 2013, and has raised about $6 million previously, lead by Fintech Ventures Fund.

It’s not the biggest real estate crowdfunding platform in the space, but it’s definitely a major player, and it’s open to all investors. Similar platforms include Fundrise and Realty Mogul,

GroundFloor’s equity crowdfunding campaign is operating under the “Regulation A” framework updated by the JOBS Act in 2015, which opens it to investment by “non-accredited” investors. Sometimes referred to as a “mini I.P.O,” it allows a private company to raise up to $50 million online through a simplified process with the SEC in the US.

My back of the envelope math: they’re selling about 15% of the company for $5M, at $10 per share, putting them at about a $33M post-money valuation.

Investors will receive common stock in the company, as well as some user perks on the platform. There is no liquidity event, dividend payment, nor secondary market, nor any other way to actually earn a return on the investment anywhere on the visible horizon, though shares could be transferred privately between investors.

Groundfloor’s current investment round closes March 23rd. There will be additional rounds, but the investment terms may change between them.

Not the first:

Other crowdfunding platforms have done similar raises using the same “Regulation A” framework for directly funding from non-accredited investors. WeFunder and StartEngine, which run equity crowdfunding platforms for startups making new products or technologies. WeFunder raised $6.8 million in 2016, while StartEngine’s self-funding campaign launched in October 2017 has so far raised $3.6 million.

Fundrise, another real estate crowdfunding platform, raised $14.5 million in 2017 via a similar self-funding “Regulation A” offering, but only made shares available to existing members of their platform.

So how does anyone actually make money with equity crowdfunding?

The time horizon on earning a return from an equity investment in a startup is much longer. It’s not about making the reliable annual 10% of traditional real estate investing; it’s about taking a long-shot chance at a 10x-100x return in 5-10 years. Many of these startups are very proud of what they’re doing, and make it clear that they are not in to try and make a quick sale of the company. Investing in startups requires patience, years of holding an illiquid investment of uncertain value on the slim chance it may become the next Tesla.

Groundfloor states the risks in their offering circular:

- “Because no public trading market for our shares currently exists, it will be difficult for you to sell your shares and, if you are able to sell your shares, you will likely sell them at a substantial discount to the public offering price.”

- “Groundfloor Finance has incurred net losses in the past and expect to incur net losses in the future. If Groundfloor Finance becomes insolvent or bankrupt, you may lose your investment.”

- “Although we do not intend to implement a liquidity transaction, we reserve the right to do so in the future. If we do not successfully implement a liquidity transaction, you may have to hold your investment for an indefinite period.”

- “We do not expect to declare dividends in the foreseeable future.”

- “Your interest in us will be diluted if we issue additional shares, which could reduce the overall value of your investment.”

- “Groundfloor Finance will need to raise substantial additional capital to fund future operations, and, if Groundfloor Finance fails to obtain additional funding, Groundfloor Finance may be unable to continue operations.”

When you invest in an equity offering like this, you are making a bet on a long time horizon that this company may eventually grow into something much bigger than it is today, and only then might it engage in the kind of liquidity event that would result in you seeing a return on your investment.

The approach professional investors take with startups is to carefully choose and invest in several, with the hope that the big payout from one or two will cover the losses from the others.

The Dark Side:

The lack of big raises in equity crowdfunding so far is also indicative of deeper problems.

Equity crowdfunding is most popular with technology startups and new consumer product companies, the same types of companies that might otherwise raise money from venture capital or angel investors, and some are the kind of thing you might see on KickStarter or Shark Tank.

The question to ask is, why would a promising startup choose to raise money via equity crowdfunding instead of from an institutional investor? There’s a lot of venture capital money out there looking for startups to invest in. A promising startup can usually line up funding from just a few institutional investors who can also bring a lot of connections and expertise that will help the startup to grow.

A popular new product can often raise lots of money via pre-sale crowdfunding on KickStarter or Indiegogo without giving any of the company away or dealing with investors and SEC compliance.

Running a crowdfunding campaign is a huge effort, including a big SEC compliance burden, and requires dealing with hundreds of unsophisticated investors who require a lot of handholding and have the potential to get very upset if things don’t go smoothly. Regulation A raises like the one Groundfloor is doing are generally cited to cost upwards of $200,000 in legal, compliance, and marketing costs.

This can result in a selection bias problem, in which only the startups turned away from the VCs and Angel investors turn to this difficult and expensive funding source of last resort: the crowd.

Investors haven’t been thrilled with crowdfunding either. The long time horizon for liquidity is tough to swallow if you’re accustomed to a stock portfolio you know the value of each day and could sell on demand. Unlike savvy venture capitalists that fight for the best investment terms and may retain a seat on the company board, crowdfund investors are stuck with the deal as presented to them, and are not always well equipped to understand issues around dilution or given much power to make decisions around liquidity. They just have to trust that on the long term, if the company does well, they should do well too.

The Long Shot:

It’s these factors combined that make the Groundfloor raise so interesting. Real estate debt crowdfunding is a solid investment, but by investing in Groundfloor itself instead of on Groundfloor, an investor who believes in the platform can take the long odds on a possible big equity payout based on the expectation that Groundfloor will continue to grow and, and one day in the far future, may be either acquired or issue a full IPO.

Groundfloor probably isn’t doing this equity crowdfunding raise because no one else would give them money. Alternative finance is one of the hottest sectors for startups to raise VC money in. We assume they’re doing it because they are already a crowdfunding platform, the machinery is already in place, and they have to believe in the value of investment crowdfunding as a philosophy. It’s what they’re built on.